Launched in 2011, Twitch.tv capitalised on the increased viewer interest in videogame commentary channels on YouTube; an increase described as ‘stratospheric’ [1: 11]. Gaming content creators such as ‘PewDiePie’ displayed unprecedented popularity [2] and the channel ‘Game Grumps’ pioneered the trend of ‘Let’s plays’ found in 2012 [3]. Distinct from ‘Long Plays’ which provide ‘nothing but the complete gameplay itself’ [4: 237], ‘Let’s Plays’ emphasise an external narrative provided through the commentary of the content creator. This narration ‘tells the story of the player rather than that of the game’ [4: 236] which contributed to the continued success of Twitch.tv.

As Twitch’s popularity grew, this ‘spin-off website from the other, more broadly focused, streaming site Justin.tv’ [5] has since attracted many content creators (and with them their fanbases) from YouTube. Currently owned by competing parent companies, ‘Amazon and Google’ respectively [6], this rivalry prompted YouTube’s limited release of its own livestreaming functionality in 2011 – allowing ‘verified accounts’ to use the feature later in 2013. [7]

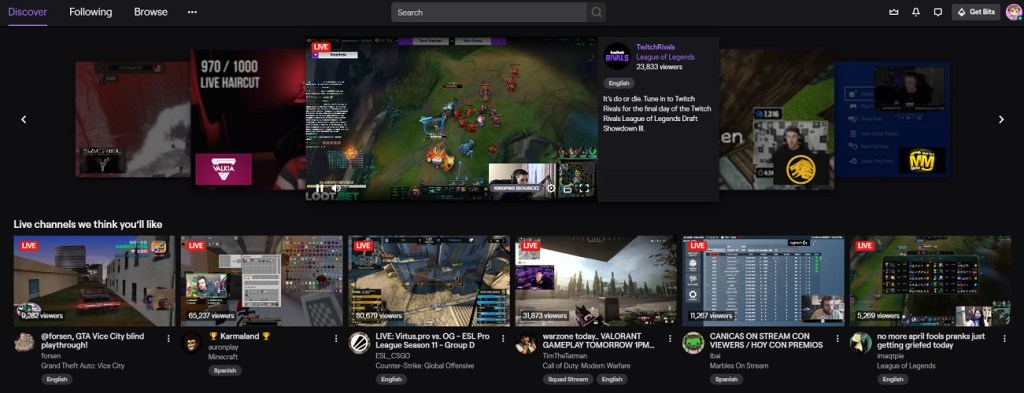

A key distinction to make when analysing Twitch’s various search pages is the intention and desires of the viewer. As is found in other streaming services such as Netflix and Amazon Prime Video, content is categorised and organised in the pursuit of streamlining the user journey through keeping ‘browsing time spent on each service page’ at a minimum. [8: 966]

In accordance to this, the more popular channels accommodate most of the landing page’s real estate and are presented boldly. These are often child-friendly streamers or conglomerate channels hosting eSports events as these will satisfy the needs of the average viewer. These are often high-definition streams with vocal personalities playing popular games such as Counter-Strike: Global Offensive (Valve, 2012) and League of Legends (Riot Games, 2009).

However, for streamers performing to viewer counts in the hundreds and thousands, maintaining a coherent conversation with any one chatter is an impossible task. One of the appeals of watching a livestream over a video-on-demand (VOD) is this interactive element that is frequently unavailable in these popular streams. The rate at which viewer messages are received results in an intangible stream of comments.

Twitch has recognised this as an issue in its implementation of ‘sub-only’ and ‘follower-only’ modes for twitch partners and affiliates. This incentivises commercial spending making both the streamer and Twitch money and, in theory, decreases the message rate to allow more cohesive conversations.

In practice, this only marginally slows promoted streams and still limits the chatter’s opportunity for interactivity. As a side note, independent streamers often support donations where the viewer can attach a message to be read out live – frequently seen as the only avenue to ask questions or spark conversation topics.

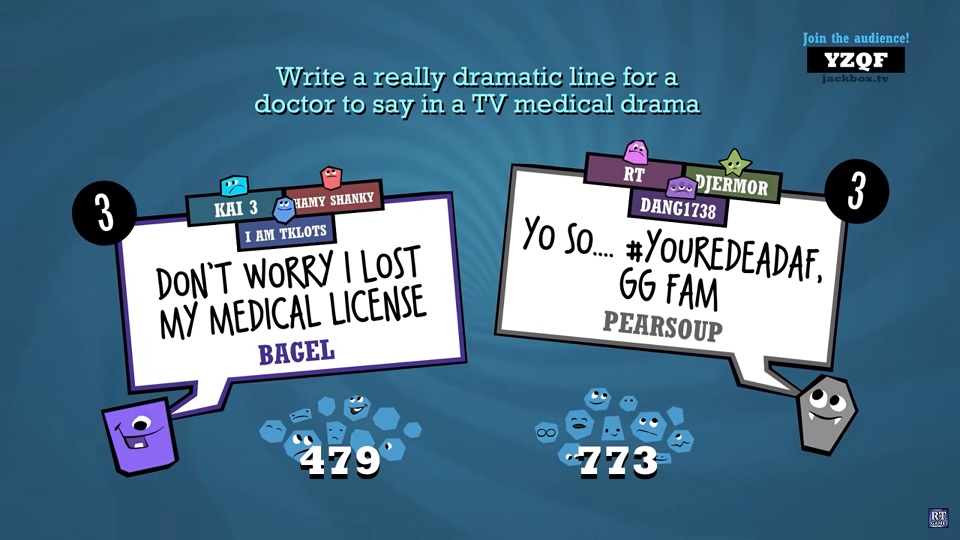

One aspect where these popular streams prosper is with online party videogames designed for large groups of people such as the Jackbox Party Pack (Jackbox Games, 2014) series. Featured titles like Quiplash allow select viewers to contribute comedic answers to prompts and the remaining audience vote on their favourites as below.

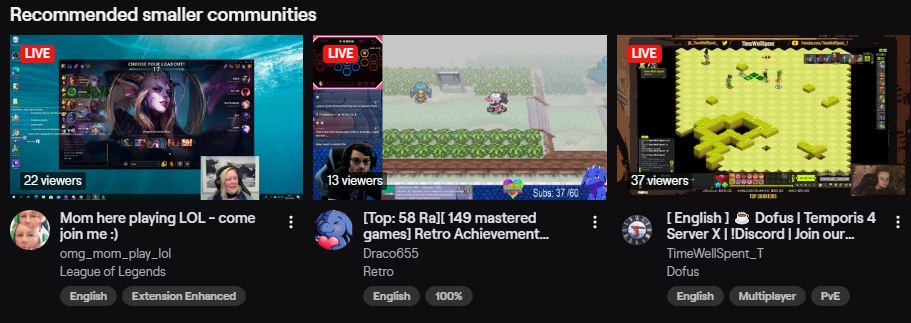

For more traditional videogames designed without a platform like Twitch in mind, viewers choose to watch a less popular channel for a number of reasons. One of these is the expectation of a stronger streamer-viewer relationship. Most streamers will converse with their chat as a means to keep them engaged with the channel and are able to do so more effectively with manageable comments. In similar recognition, Twitch also hosts a number of ‘recommended smaller communities’ further down their landing page for this group of chat expectant ‘vicarious viewers’. [5]

To conclude, streams with lower average view counts often boast higher rates of active ‘chat engagement’ [5] and streamers hosting smaller communities are able to satisfy the needs of their fanbase more effectively. [9: 6] As a modest streamer with 234 followers [10] the high production quality found in popular channels is substituted for consistent viewer engagement allowing for an entertaining broadcast where fans can expect elements of interactivity. [4: 252]

Bibliography

[1] Miller, M. (2011) YouTube for Business: Online Video Marketing for Any Business, London: Pearson Education, 2nd ed, p. 11.

[2] https://www.youtube.com/user/PewDiePie/videos?view=0&sort=da&flow=grid PewDiePie. Retrieved 2020-04-01.

[3] https://www.youtube.com/user/GameGrumps/videos?view=0&sort=da&flow=grid Game Grumps. Retrieved 2020-04-01.

[4] Kerttula, T. (2016) ‘What an Eccentric Performance: Storytelling in Online Let’s Plays’ in Games and Culture, Vol. 14, Iss. 3, pp. 236-255.

[5] Anderson, S. (2017) ‘Watching People Is Not a Game: Interactive Online Corporeality, Twitch.tv and Videogame Streams’, Game Studies: The International Journal of Computer Game Research, 17:1, Available at: http://gamestudies.org/1701/articles/anderson

[6] Geeter, D. (2019) ‘Twitch created a business around watching video games — here’s how Amazon has changed the service since buying it in 2014’, CNBC Gaming, Available at: https://www.cnbc.com/2019/02/26/history-of-twitch-gaming-livestreaming-and-youtube.html

[7] Lungden, I. (2013) ‘YouTube Opens Up Live Streaming And Google+ Hangouts On Air To All Verified Accounts’, Tech Crunch, Available at: https://techcrunch.com/2013/12/12/youtube-opens-up-livestreaming-and-google-hangouts-on-air-to-all-verified-accounts/

[8] Elkhatib, Y. et al., (2014) ‘Just Browsing? Understanding User Journeys in Online TV’, Association for Computing Machinery, pp. 965-968.

[9] Wulf, T., Schneider, F. & Beckert, S. (2018) ‘Watching Players: An Exploration of Media Enjoyment on Twitch’, Games and Culture, pp. 1-19.

[10] https://www.twitch.tv/corkintv CorkinTV. Retrieved 2020-04-02.