Dōbutsu no Mori (Nintendo, 2001)’s development aimed to produce a video game that enforced elements of ludus rooted in the player’s real-time – while allowing for paidea by limiting its dictated narrative. Despite going against the ‘triple A’ goal-oriented formula, the game became the Nintendo 64’s 28th best-selling game – spurring an enhanced port the following year, Dōbutsu no Mori+ (2002). This port was released on the Nintendo Gamecube which became the source of the western localised release: Animal Crossing (2002).

Animal Crossing is a unique role playing game which focuses on daily activities designed to capture the player’s attention year-round [1]. From seasonal events, time-specific collectibles and consistent non-player-character routines, Animal Crossing prides itself in its steady pacing and the player’s freedom to ‘live life in an innovative experience that’s a world of its own’ [2]. During their 2002 E3 press conference, Nintendo’s marketing emphasised this idea that: ‘you get to decide what to do.’ [3: 16:08]. The advertising developed this trend by showcasing the physical gameplay options at the player’s disposal:

The bug-catching and fishing are simple quick-time-events while the fruit harvesting and fossil collecting are more time-consuming than challenging. Without much of a dictated narrative or an enforced time constraint, the player is able to explore these mechanics at their own pace. Critics often praised how limitless the game felt as a result of this limited time-locked approach to gameplay – one likened Animal Crossing’s light-hearted routine structure to ‘being addicted to sugar but never getting sick’ [4].

The game’s soundtrack embodies this relaxed style in its minimalist tracks focusing on melodies that emphasise the space between notes. As each three minute song is designed to play for an hour in real-time, the music is deliberately simple (rarely deviating from a major scale) as to not overwhelm the player or have them focus on distracting musical accents.

Note the brevity of each note to accentuate a feeling of emptiness

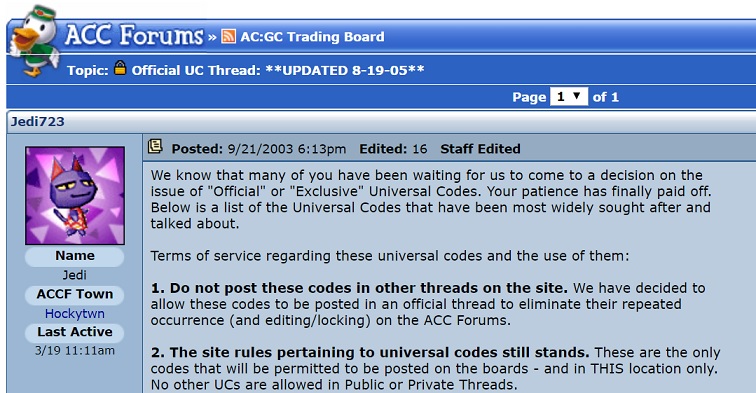

Other than for the player’s own satisfaction, these seemingly menial tasks do little to keep the player invested. Arguably, the overwhelming force in the game’s ‘addictive’ play style is its social implications. In researching the games’ forums, the majority of contributors include their ‘town ID’ in their signature – allowing others to visit their instance. With the knowledge that, at any time, a stranger could interact and judge your town could factor into a player’s need to login daily.

http://www.animalcrossingcommunity.com/Topic/32800/1/Official_UC_Thread_UPDATED_8_19_05_

This has been further implemented in each of the series’ later games and has become a selling point in Animal Crossing: New Horizons (Nintendo, 2020); implementing social media sharing, eight-player cooperative play and advertisement of the game’s hashtags (#ACNH #AnimalCrossing). The state of the player’s home/village has become increasingly more about how their peers will view their progress more than a sense of personal satisfaction.

This often leads to two conclusions depending on the gamer’s preferred playstyle:

- A goal-oriented player will construct their own narrative end to strive towards. For Animal Crossing, this is often: furnishing the perfect home, paying off all debt, cultivating the perfect village or completing the museum.

- A non-goal-oriented player sees Animal Crossing as a form of escapism which ties into the game’s daily ‘menial yet relaxing’ tasks [5: 9].

Kim suggests the appeal is in non-goal-oriented ‘joy of playing a slow-paced game for pure pleasure’ [6: 365]. Borrowing McMahan’s interpretation of video-game immersion, Animal Crossing’s laid back focus on player freedom allows ‘the player [to be] caught up in the world of the game’s story (the diegetic level)’ [7: 68]. These categories can be compared to Wark’s distinction between ‘triflers’ and ‘cheats’ when discussing the approach to goals in The Sims (Maxis, 2000) – arguing that simulation games ‘offer a perfect unfreedom, a consistent set of constraints’ [8: 40].

In summary, Animal Crossing’s ludicinnovation succeeded in constructing a videogame with its rules tied to the routine of the real-world. In doing so, ‘the pleasure experienced by the player, the paidea’ [9], is achieved through the game’s theme of relaxation and freedom. The element of time that ludically restricted player opportunity through seasonal events simultaneously allowed for unlimited replay-ability and unparalleled player freedom.

Bibliography

[1] Rojas, A. (2000) Animal Crossing, Nintendo World Report, Available at: http://www.nintendoworldreport.com/hands-on-preview/2855/animal-crossing-gamecube

[2] Nintendo. (2003) ABOUT THE GAME: Animal Crossing, Nintendo Power, Available at: https://web.archive.org/web/20030213033234/http://www.nintendo.com/games/gamepage/gamepage_main.jsp?gameId=646&showMe=1

[3] Nintendo. (2002) Nintendo E3 2002 Press Conference from PGC E3 2002 DVD, Planet Gamecube, Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6uzTeRvm1Uo

[4] Trais, J. (2002) ‘Animal Crossing’, Electronic Gaming Monthly, 158:2, Available at: https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A109514697/ITOF?u=derby&sid=ITOF&xid=4cda6ab9.

[5] Donato, A. (2018) ‘Mobile Madness: How Animal Crossing Made Me Actually Do Self-Care’, Broken Pencil, 78:1, p. 9, Available at: https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A529123880/ITOF?u=derby&sid=ITOF&xid=fc251b9b

[6] Jin, K. (2014) ‘Interactivity, user-generated content and video game: an ethnographic study of Animal Crossing: Wild World’, Continuum, 28:3, pp. 357-370.

[7] Mcmahan, A. (2003) ‘Immersion, engagement, and presence: A method for analyzing 3-D video games’, The Video Game Theory Reader, pp. 67-86.

[8] Wark, M. (2007) Gamer Theory, London: Harvard University Press, pp. 26-50, Available in part at: http://www.futureofthebook.org/gamertheory2.0/index.html@cat=2&paged=3.html

[9] Lalande, A. (1928) ‘Vocabulaire technique et critique de la philosophie’, Paris: Librairie Félix Alcan, in Frasca, G. (1999) ‘LUDOLOGY MEETS NARRATOLOGY: Similitude and differences between (video)games and narrative.’, Available at: https://ludology.typepad.com/weblog/articles/ludology.htm